Life, Novels

A CENTURY AND A HALF SINCE THE BIRTH AND 115 YEARS SINCE THE DEATH OF SVETOLIK RANKOVIĆ (1863-1899), WRITER OF ”MOUNTAIN EMPEROR” AND ”PICTURES FROM LIFE”

Late Offspring of Ancient Times

He stepped on the literary scene of Serbian realism in its final phase, at the very end of the XIX century. He graduated from the Spiritual Academy in Kiev. Aware of the inside of upcoming capitalism, before which old values, both personal and social, disappeared, he tried to defend himself with idyll and pessimism. He knew it was in vain. He also knew that everything he was speaking about will become clear only much, much later. He did not even sculpt with hatred the images of those who killed his parents, even them he did not leave without hope

By: Uroš Matić

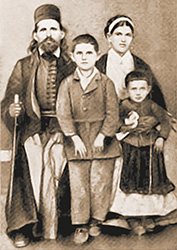

Svetolik Ranković was born in 1863, in Moštanica, near Belgrade, where his father Pavle worked as a teacher. Soon afterwards, Pavle became a priest, and the family moved to the village of Garaši near Aranđelovac. There, in the heart of Šumadija, Svetolik grew up and learned to love the life in the country. Most of his novels and stories take place in the area between Bukulja, Venčac and Kosmaj, staying close to his homeland in this way as well. Svetolik Ranković was born in 1863, in Moštanica, near Belgrade, where his father Pavle worked as a teacher. Soon afterwards, Pavle became a priest, and the family moved to the village of Garaši near Aranđelovac. There, in the heart of Šumadija, Svetolik grew up and learned to love the life in the country. Most of his novels and stories take place in the area between Bukulja, Venčac and Kosmaj, staying close to his homeland in this way as well.

The tradition of a priest’s family determined Ranković’s path: after lower gymnasium and theology school in Belgrade, he went to Kiev (Russia) in 1884 to continue studying theology and graduated from the Spiritual Academy. In 1889, the year when king Milan Obrenović abdicated in favor of his son Aleksandar, Svetolik returned to Serbia and began teaching religious education in the Kragujevac gymnasium. A year later, in 1890, he passed the professor exam with his essay On Church Rhetoric, with the highest grade. In 1892, in Homeland, he published his story ”Autumn Pictures”, which provoked great interest.

As member of the Radical Party and opponent of the regime of Aleksandar Obrenović, he was often transferred, ”not to grow roots anywhere”, and obstructed in his career. He was transferred from Kragujevac to Belgrade in 1893, and already in 1894 to Niš. Three years later, in the crucial year of 1897, his first novel Mountain Emperor was published as the thirty-eighth book in the Serbian Literary Cooperative edition ”Kolo”. He managed to return to Belgrade the same year and get a job as gymnasium teacher of religious education, but not for long. His status was insecure, and his position more resembled mocking: ”interim acting part-time teacher”. He was deeply unsatisfied and intended to leave his vocation. That same year of 1897, his tuberculosis began taking over, so he retreated to recuperate, first to Garaši.

In the first half of the following year, he looked for sanctuary in the monastery of Bukovo, where he wrote The Village Teacher, his second novel. In autumn, following his doctor’s advice, he went to Herceg-Novi, hoping that the sun, sea and pine trees will slow down the advancement of the fatal disease. There he wrote the ”Old Cherry Tree”, perhaps his best story. He began his novel Broken Ideals (original title was Monk). News came: ”The Village Teacher was first awarded by Matica Srpska, and then by Kolarac Foundation, which also printed it.” In the first half of the following year, he looked for sanctuary in the monastery of Bukovo, where he wrote The Village Teacher, his second novel. In autumn, following his doctor’s advice, he went to Herceg-Novi, hoping that the sun, sea and pine trees will slow down the advancement of the fatal disease. There he wrote the ”Old Cherry Tree”, perhaps his best story. He began his novel Broken Ideals (original title was Monk). News came: ”The Village Teacher was first awarded by Matica Srpska, and then by Kolarac Foundation, which also printed it.”

He looked for a cure, light and peace, but didn’t find it. Amidst everything that made the darkness even thicker, his youngest son also died. Immediately afterwards, in 1899, he returned to Belgrade. He was writing to his very last moment, in his death bed. He was finishing his novel Broken Ideals, published in 1900, post-mortem, by Serbian Literary Cooperation, as the sixty-second book of the ”Kolo” edition.

Even on March 18, 1899, on the day he died, he was holding a pen in his hand. ”A pen with which he wanted to bring enlightenment and education, in a hand that knew to excuse and forgive.”

He was only thirty-six.

His works, as a late offspring of old times, end realism in Serbian literature and anticipate a new époque: modern art.

SORROW COVERING EVERYTHING

It could be said that Svetolik Ranković passed through the Russian school of realism. He interest in literature increased while he was a student of the Spiritual Academy in Kiev, ”the mother of Russian cities”. He wrote poetry, translated Russian literary masters. It was where he wrote ”The Captain’s Wife”, his first novel, in 1885. Turgenev and Tolstoy, Goncharov and Shchedrin, Gogol and Dostoyevsky clearly influenced him. Even Ranković’s contemporaries, Andra Gavrilović and Jovan Skerlić, wrote about that influence, as well as Milorad Najdanović and Miljko Jovanović half a century later. (They, however, neglected the similarities between Svetolik Ranković and writers from Western literatures, such as Balzac and Flaubert.) Unlike Gavrilović, who emphasizes the influence of Tolstoy, Jovanović, in his master thesis People of Weak Will in the Works of Svetolik Ranković emphasizes, like Skerlić, Turgenev: ”He had the same gentle warmth and love for his heroes as Turgenev did; he participated in their sufferings as Turgenev did; he lamented over their futile lives as Turgenev did. And they both possessed the almost female sensitivity and affinity to study people of weak will.” It could be said that Svetolik Ranković passed through the Russian school of realism. He interest in literature increased while he was a student of the Spiritual Academy in Kiev, ”the mother of Russian cities”. He wrote poetry, translated Russian literary masters. It was where he wrote ”The Captain’s Wife”, his first novel, in 1885. Turgenev and Tolstoy, Goncharov and Shchedrin, Gogol and Dostoyevsky clearly influenced him. Even Ranković’s contemporaries, Andra Gavrilović and Jovan Skerlić, wrote about that influence, as well as Milorad Najdanović and Miljko Jovanović half a century later. (They, however, neglected the similarities between Svetolik Ranković and writers from Western literatures, such as Balzac and Flaubert.) Unlike Gavrilović, who emphasizes the influence of Tolstoy, Jovanović, in his master thesis People of Weak Will in the Works of Svetolik Ranković emphasizes, like Skerlić, Turgenev: ”He had the same gentle warmth and love for his heroes as Turgenev did; he participated in their sufferings as Turgenev did; he lamented over their futile lives as Turgenev did. And they both possessed the almost female sensitivity and affinity to study people of weak will.”

Similar to these great role models, Ranković weaved his philanthropy into his heroes, however didn’t get lost in foggy and abstract mercy, says Najdanović, but loved and felt compassion for the specific man of the Serbian lands, preserving originality.

The influence of Serbian literary tradition is clear in the work of Svetolik Ranković.

”The influence of Serbian poetic realists, such as Vojislav Ilić (lyrically intonated autumn pictures), Milovan Glišić (witty stories in the folk manner), Laza Lazarević (psychological stories), Radoje Domanović (satirical attitude towards the rural society and bureaucracy) is obvious in his stories. Also significant is the influence of symbolic stories of Simo Matavulj.” ”The influence of Serbian poetic realists, such as Vojislav Ilić (lyrically intonated autumn pictures), Milovan Glišić (witty stories in the folk manner), Laza Lazarević (psychological stories), Radoje Domanović (satirical attitude towards the rural society and bureaucracy) is obvious in his stories. Also significant is the influence of symbolic stories of Simo Matavulj.”

The life and world of Svetolik Ranković belonged to a different order of values from the one brought by the contours of the upcoming époque. From economic inequality deepened by capitalism also in the rural areas, from selfishness and soullessness, babbittry and hypocrisy, incorrectness in the state and in the church, he first tried to defend with idyll and old social and family values. He glorified the honor and purity of rural areas from the past times and described the contemporary era in an opposite manner, which could be seen in his stories ”The Village Benefactor”, ”Devil’s Business”, ”Friends” and ”Official Correction”. The course of history, however, could not be stopped.

”It is difficult to find more sincere pessimism in our literature, in which, especially lately, pessimism became a common place”, wrote Skerlić about Ranković. ”His life and illness developed the seeds of pessimism and the older he was, his views were more pessimistic. Fighting for a piece of bread, in which one wastes his best energy and which ruins pride, moving from one part of Serbia to the other, illness of his children and frequent deaths, especially the illness he carried in his chest, made him increasingly sorrowful and despondent.”

THE COMPLEX SIMPLICITY OF TRUTH

Pavle Stevanović also explained the pessimism of Svetolik Ranković with mainly personal reasons. Others, such as Živojin Boškov, find the focus of that feeling in social circumstances. The opinions of many authors about it, many ideological, political and dynastic hints could be found, which certainly don’t lead us to ”the complex simplicity of truth”. There is, undoubtedly, also the interweaving of personal and social sorrowful reasons. Skerlić himself, although he frowned at pessimism, describes the atmosphere only four years after Ranković’s death, in the eve of the May Overthrow:

”There is not enough space, the air has become thin and suffocating, appetites have grown tremendously, ambitions incredibly wild, people have become evil to each other as never before, and in the pushing and shoving, all consideration has been lost, all feelings of human brotherhood. We became like a crowd of starving wolves, who, howling, began tearing each other.”

Such was an event from Ranković’s youth, which had an important influence on his life, view of the world and his literature. He was a student in Kiev and spent his summer vacation of 1886 in his homeland, when tragedy struck him and his family. Robbers attacked his house and killed his parents. He managed to run away and bring help, but it was too late. He described similar circumstances a decade later in his novel Mountain Emperor, depicting how robbers plundered master-Đorđe: Such was an event from Ranković’s youth, which had an important influence on his life, view of the world and his literature. He was a student in Kiev and spent his summer vacation of 1886 in his homeland, when tragedy struck him and his family. Robbers attacked his house and killed his parents. He managed to run away and bring help, but it was too late. He described similar circumstances a decade later in his novel Mountain Emperor, depicting how robbers plundered master-Đorđe:

”Blood rushed down Đorđe’s face, and he immediately, like a beast, ran to the villain and thrust a knife into his shoulder. Radovan burst, his eyes blazed like a tiger’s, and he jumped aside from furious Đorđe. He raised his rifle, and just as he was about to stretch his arm, another scream was heard in the house. Đorđe’s youngest son fled from the house, covered in blood, with Sremac running after him with a bare knife. The child ran straight to his father, screaming from the top of his lungs. Đorđe, seeing his beloved son in blood and a knife swaying after him, rushed like a wild cat to Sremac and shoved the knife into his chest. The villain fell down, but in the same moment Radovan triggered the rifle, Đorđe swung to the side and fell.”

In the experience of young Svetolik, this was not just a horrible crime of a robbers’ gang. The event had a much deeper meaning, symbolic, (meta)historical and social. The personal tragedy didn’t blur the sharpness of the writer’s view, nor has it taken him to wrong directions. He depicts the leader of the gang in the Mountain Emperor,Đurica, in a complex manner, with all his internal dramas. Although an outlaw, he is not just a banal criminal and provokes sympathy in the reader with his longing for purity. The reader is afraid for him. There is no catharsis in Ranković’s work, as with Russian realists, the negative character doesn’t become a moral hero, however he’s also not a disgusting villain. He is, simply, a human! And the entire drama of the world always and again weaves and entangles around him. <

***

Deliriously

He had to think and write fast, not characteristic for his age. Pressured by his illness, incurable at the time, he was forced to act quickly, even deliriously. He wrote the ”The Village Teacher” in two and ”Broken Ideals” in only three months.

***

Love is a Creating Force

Ranković built his personal experience of a neglected and persecuted officer of the Obrenović administration into his description of the life of a teacher in ”The Village Teacher”. He opposed the glorious old-time ethics, superior although almost extinct, to malice, blackmails and low instincts of the ”new age”. He unmasks the life of hypocritical priests and fake ascetics in ”Broken Ideals” by confronting it with the strong character of the Orthodox priest in the ”Mountain Emperor”, who gives fatherly advice to the robber and tries to lead him towards genuine redemption. Svetolik Ranković did not even sculpt with hatred the characters of those who killed his parents, even them he did not leave without hope.

|